This one has been brewing a while but I think the clearest framing comes from The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas (don’t worry it’s a short read). Tldr; Is there any amount of civic good, the peace and prosperity of Omelas that can justify a morally indefensible action, the intentional pain and neglect inflicted on a single feeble-minded child? I mentioned this in my travelogue on Korea but I think it’s a useful framing for all nature of moral problems that beset the application of moral principles in individuals and societies at large.

For the individual, I think Viktor Frankl provides a nice version of this:

Life is like being at the front line in a battle where the forces are not always lined up on the same sides. This is perhaps best illustrated by the experience of another man, a young fellow I once knew, who had to make the tragic decision whether to sacrifice himself to the German war machine or stay with his elderly mother who was completely dependent upon him. He told me that he asked himself: 'Where does my duty lie? - Viktor Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning

Herein lies the problem with arguments based on morality:

Moral arguments are fundamentally intractable without a recourse to individual values: nobody except our young man can decide whether his duty is to country or his mother there is no empirical framework that can be defined to solve this issue. While he has some internal freedom to make this decision the problem cannot be solved in the abstract without recourse to one’s preexisting moral values.

Moral arguments are binary, absolutist, and non-quantitative in nature: If you believe eating meat is immoral there is not a amount of daily consumption that becomes moral. If you believe intentionally harming a defenseless child is immoral no amount of civic good can compensate for that.

Moral arguments are fragile: Moral values shift from person to person, nation to nation, and change over time. Any policy based on moral judgments inherently rests on an unstable foundation of perception.

Moral arguments are poisonous to compromise. Both sides believe themselves to be in sole possession of an unassailable high ground and their opponents to be fundamentally lacking.

Now I’m not suggesting moral arguments should disappear. That goal is neither tenable nor desirable. As numerous psychological studies have shown moral thinking is deeply ingrained in us and certainly plays a role in social cohesion. Also, I admit at least the possibility, we are capable of moral persuasion at an individual level if we encounter a novel moral argument that, importantly, aligns with our preexisting values and has a minimum of cognitive dissonance e.g. What would Jesus do? (WWJD) to a Christian.

But the problem, as we’ve noted is that while individuals can solve moral equations and can even be swayed by novel moral arguments provided they fit within their existing system of values, they become fundamentally intractable for societies at large. Different values simply talk past each other. Those who say “honor thy father and mother” cannot persuade by moral argument those who say “serve your country” and vice versa. And the absolutist nature of moral arguments leads inevitably to reductio ad absurdum arguments such as what we encounter in Omelas or in any number of scenarios with deep historical roots taking the form of “How much resource Y is the suffering of people X worth” or “How many Q can atone for the death of P”.

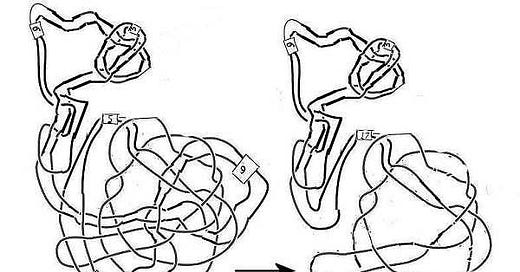

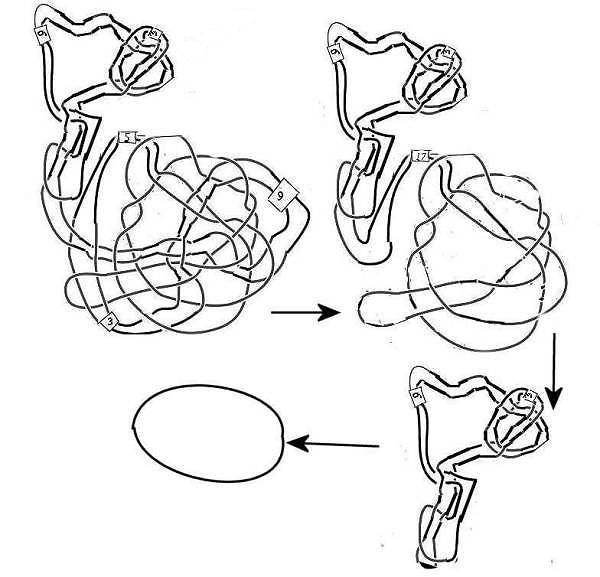

I apologize for the excessively abstract phrasing but if I’m trying to rid policy proposals of their moral trappings it would hardly do well for me to start making moral arguments. But taking a look at the internecine conflict in Israel/Gaza we can see how of overlapping historical, religious, and contemporary moral value judgements make up a huge number of unreconcilable moral questions that routinely make a mockery of any attempt to devise a solution and tie up the entire discussion in an impenetrable Gordian knot.

This is why I posit: Moral arguments make for bad policy. And the sword of Alexander in this case that can split our Gordian knot is to strip away the moral dimension of the problem when negotiating and making policy decisions that can be both nuanced and make reference to concrete benefit.

At the extreme, our civic government in Omelas is making a very clear-eyed calculation. Thankfully, in real-world situations the cost-benefits are generally less magical changes to policy directly affect people for better or worse there’s not a child we can lock in a broom closet to solve all our problems.

While I’m not suggesting I’ve solved the Middle East various empirical forms of a two-state solution (or something else) become tractable once we restrict our aim to the empirical “greater good” for the current inhabitants of the region freed from also needing to solve the baggage of history, religion, ethos, and culture.

Now there are numerous objections that can be leveled here.

The first is to take something with a clear and near-unanimous moral position, what slippery, subjective ground, how near the precipice, and say how dare you suggest we should not use this argument in crafting policy. Slavery in the United States is a perfect case for this although discrimination based on sexual orientation would also fit the bill for most of the audience.

And, indeed, it does feel fairly ridiculous to say “slavery is an abomination” should not be part of the debate to abolish slavery. But, again, that argument only works for persuading the already like-minded. I don’t see anything in the historical record that shows that moral argument for abolishing slavery were effective, to the contrary it seems they made the disagreement more intractable and hardened opposing positions.

For both slavery and sexual non-discrimination between consenting adults there is a concise, cogent and largely universal case for letting people do and say whatever they want as long is it does no harm to others. This argument is both more universal and more unassailable because it does not require moral persuasion.

While I don’t agree with people whose religious values lead them to believe that homosexuality is a sin, I can ignore that argument and not entrench them further in their position by trying to stake my own position on an opposing moral high ground. I can simply point to the values of free movement of people, capital, and goods and costs of enforcement, discrimination, and harm amplification. My argument is stronger, more generally applicable, more stable, and less polarizing for being shorn of it’s moral dimension.

A second objection is that this framework is distasteful or immoral. That it is inhuman to assign a dollar value to a life or make a statement like the life of one American is worth more than 100 Somalis. Absolutely! There’s no doubt that this method of operating is pretty antithetical to individual human interactions and thinking.

We would, individually, be the lesser for reducing our fellow humans to dollar values. But at the level of society and government this calculus makes intractable moral problems tractable calculations; and most importantly, allows us the get better outcomes and make real improvements.

Questions about housing, healthcare, war, peace, literacy, all lose their moral dimension and become tractable. Even better I’d argue there is a positive feedback loop here where by maximizing the “worth” of their citizens, individuals and nations benefit. So while allotting value to human lives is distasteful, the alternative of not doing so is tremendous harm, suffering, and stasis.

Politics is not the art of the possible. It consists in choosing between the disastrous and the unpalatable. - John Kenneth Galbraith

A final objection we’ll touch on is one of the most common but most unworthy. The first variant of this is similar to the hand-wringing around AGI that by somehow abandoning moral reasoning we’ll end up with paradoxical conclusions such as eliminating half of the population to maximize the happiness of the remaining half. I don’t think there’s really much to say except that these sorts of conclusions rest on tortured reasoning and we probably don’t need to be concerned about them until we see some possibility of them occurring.

The other variant is that without moral guidance we will somehow be left adrift unable to tell benefit from harm, good from evil— like the apocryphal atheist freed from religion, who, without the risk of damnation and the lure of paradise, is untethered from morality. All the evidence we have is that moral behavior is embedded deeply in our genetics and our culture. And while the “greatest good” will always be debatable at the level of individuals and groups it seems to beggar belief that stripping policy and debate of moral arguments would eliminate them in us as individuals.

Summary

So to summarize when we abandon moral arguments in our policy proposals:

The moral grounds on which to challenge the proposal are eliminated

The efficacy of the proposal can be explicitly tested. The most moral policy that leaves us as a society worse off is worthless.

Irreducible questions of history, philosophy, and morality are converted into soluble empirical questions based on the “world as it is”.

Intractible qualitative values such as the value of human life or freedom can be converted to tractable quantitative questions (albeit without completely eliminating uncertainty).

A question of what is “right” is converted into a question of what is “effective”.

Examples

I wanted to go with some smaller and less all encompassing examples to see this process in practice.

The University of California (UC) system’s admission criteria provides a great example of an effective policy separated from it’s moral dimension. Although it remains a contentious issue, as a result of Proposition 209, the UC system has been required to craft a race-blind admission policy that addresses contemporary inequalities without explicit racial factors or motivation.

Academic accomplishments in light of your life experiences and special circumstances, including but not limited to: disabilities, low family income, first generation to attend college, need to work, disadvantaged social or educational environment, difficult personal and family situations or circumstances, refugee status or veteran status.1

I won’t say that the UC system has solved “equity” but by explicitly abandoning a moral argument in their analysis and building one based on this more concrete form of the greater good (equity) they’ve developed something that is less controversial and, arguably, more effective.

Contrast this with something like Harvard’s policy which until recently did explicitly take into account race while this project may have salved some consciences and remediated some historical inequality it was extremely contentious and did not really act to improve equity since the while the resulting cohorts were more racially biased the socioeconomic separation was if anything more extreme.

Another example that comes to mind is Indonesia’s ongoing divisive racial policies. Policies that perhaps at the time, tried to remedy historical injustices to the Malay majority by an explicit racial criteria now act as a permanent wedge since the inherent moral logic can never be answered when has a historical injustice been remedied?

Conclusion

Our prescription may seem quixotic to make us better through less use of moral reasoning but hopefully I’ve at least opened the possibility that it leads to more attainable, effective, and stable policy because the realpolitik, empirical arguments in favor of a position are more clear, effective, and persuasive. And by explicitly excluding moral arguments from the framing you eliminate your opposition’s ability to deadlock the debate on opposing moral grounds.

I was going to include sections from this elsewhere thinking about Martin Luther King Jr.’s use of James Russell’s The Present Crisis:

Truth forever on the scaffold, wrong forever on the throne. Yet that scaffold sways the future

In thinking about the limitation of moral arguments. But the piece that spoke to me most re-reading the poem was the conclusion:

New occasions teach new duties; Time makes ancient good uncouth;

They must upward still, and onward, who would keep abreast of Truth;

Lo, before us gleam her camp-fires! we ourselves must Pilgrims be,

Launch our Mayflower, and steer boldly through the desperate winter sea,

Nor attempt the Future's portal with the Past's blood-rusted key.

Morality may indeed be our most ancient good but we must keep abreast of truth and steer ourselves upward and onward and not “attempt the Future's portal with the Past's blood-rusted key”.

As always your thoughts are appreciated. Are there other examples you think demonstrate the difficulty with moral reasoning? Do you have a scenario where you believe moral reasoning is essential to beneficial outcomes? Do you believe the position taken here is untenable? How can we shape policy debates with an aim of eliminating moral stigma?

University of California: How applications are reviewed